Pat Nixon

Pat Nixon | |

|---|---|

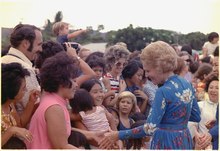

Nixon in 1972 | |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In role January 20, 1969 – August 9, 1974 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Lady Bird Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Betty Ford |

| Second Lady of the United States | |

| In role January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961 | |

| Vice President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Jane Hadley Barkley |

| Succeeded by | Lady Bird Johnson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thelma Catherine Ryan March 16, 1912 Ely, Nevada, U.S. |

| Died | June 22, 1993 (aged 81) Park Ridge, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Resting place | Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

Thelma Catherine "Pat" Nixon (née Ryan; March 16, 1912 – June 22, 1993) was First Lady of the United States from 1969 to 1974 as the wife of President Richard Nixon. She also served as the second lady of the United States from 1953 to 1961 when her husband was vice president.

Born in Ely, Nevada, she grew up with her two brothers in Artesia, California, graduating from Excelsior Union High School in Norwalk, California in 1929. She attended Fullerton Junior College and later the University of Southern California. She paid for her schooling by working multiple jobs, including pharmacy manager, typist, radiographer, and retail clerk. In 1940, she married lawyer Richard Nixon and they had two daughters, Tricia and Julie. Dubbed the "Nixon team", Richard and Pat Nixon campaigned together in his successful congressional campaigns of 1946 and 1948. Richard Nixon was elected vice president in 1952 alongside General Dwight D. Eisenhower, whereupon Pat became second lady. Pat Nixon did much to add substance to the role, insisting on visiting schools, orphanages, hospitals, and village markets as she undertook many missions of goodwill across the world.

As first lady, Pat Nixon promoted a number of charitable causes, including volunteerism. She oversaw the collection of more than 600 pieces of historic art and furnishings for the White House, an acquisition larger than that of any other administration. She was the most traveled first lady in U.S. history, a record unsurpassed until 25 years later. She accompanied the president as the first first lady to visit China and the Soviet Union, and was the first president's wife to be officially designated a representative of the United States on her solo trips to Africa and South America, which gained her recognition as "Madame Ambassador"; she was also the first first lady to enter a combat zone. Though her husband was re-elected in a landslide victory in 1972, her tenure as first lady ended two years later, when President Nixon resigned amid the Watergate scandal.

Her public appearances became increasingly rare later in life. She and her husband settled in San Clemente, California, and later moved to New Jersey. She suffered two strokes, one in 1976 and another in 1983, and was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1992. She died in 1993, aged 81.

Early life

[edit]Thelma Catherine Ryan was born in 1912 in the small mining town of Ely, Nevada.[1] Her father, William M. Ryan Sr., was a sailor, gold miner, and truck farmer of Irish ancestry; her mother, Katherine Halberstadt, was a German immigrant.[1] The nickname "Pat" was given to her by her father, because of her birth on the day before Saint Patrick's Day and her Irish ancestry.[1] When she enrolled in college in 1931 she started using the name "Pat" (and occasionally "Patricia") instead of "Thelma" but she did not legally change her name.[2][3]

After her birth, the Ryan family moved to California, and in 1914 settled on a small truck farm in Artesia (present-day Cerritos).[4] Thelma Ryan's high school yearbook page gives her nickname as "Buddy" and her ambition to run a boarding house.[5]

She worked on the family farm and also at a local bank as a janitor and bookkeeper. Her mother died of cancer in 1924.[6] Pat, who was only 12, assumed all the household duties for her father (who died himself of silicosis 5 years later) and her two older brothers, William Jr. (1910–1997) and Thomas (1911–1992). She also had a half-sister, Neva Bender (1909–1981), and a half-brother, Matthew Bender (1907–1973), from her mother's first marriage;[1] her mother's first husband had died during a flash flood in South Dakota.[1]

Education and career

[edit]After graduating from Excelsior High School in 1929, she attended Fullerton College. She paid for her education by working odd jobs, including as a driver, a pharmacy manager, a telephone operator, and a typist.[1][7] She also earned money sweeping the floors of a local bank,[1] and from 1930 until 1931, she lived in New York City, working as a secretary and also as a radiographer.[6]

Determined "to make something out of myself",[8] she enrolled in 1931 at the University of Southern California (USC), where she majored in merchandising. A former professor noted that she "stood out from the empty-headed, overdressed little sorority girls of that era like a good piece of literature on a shelf of cheap paperbacks".[9] She held part-time jobs on campus, worked as a sales clerk in Bullock's-Wilshire department store,[10] and taught touch typing and shorthand at a high school.[6] She also supplemented her income by working as an extra and bit player in the film industry,[11][12] for which she took several screen tests.[13] In this capacity, she made brief appearances in films such as Becky Sharp (1935), The Great Ziegfeld (1936), and Small Town Girl (1936).[13][14] In some cases she ended up on the cutting room floor, such as with her spoken lines in Becky Sharp.[13][15] She told Hollywood columnist Erskine Johnson in 1959 that her time in films was "too fleeting even for recollections embellished by the years" and that "my choice of a career was teaching school and the many jobs I pursued were merely to help with college expenses."[15] During the 1968 presidential campaign, she explained to the writer Gloria Steinem, "I never had time to think about things like... who I wanted to be, or who I admired, or to have ideas. I never had time to dream about being anyone else. I had to work."[16]

In 1937, Pat Ryan graduated cum laude from USC with a Bachelor of Science degree in merchandising,[1] together with a certificate to teach at the high school level, which USC deemed equivalent to a master's degree.[17] Pat accepted a position as a high school teacher at Whittier Union High School in Whittier, California.[11]

Marriage and family, early campaigns

[edit]While in Whittier, Pat Ryan met Richard Nixon, a young lawyer who had recently graduated from the Duke University School of Law. The two became acquainted at a Little Theater group when they were cast together in The Dark Tower.[6] Known as Dick, he asked Pat to marry him the first night they went out. "I thought he was nuts or something!" she recalled.[18] He courted the redhead he called his "wild Irish Gypsy" for two years,[19] even driving her to and from her dates with other men.[8]

They eventually married on June 21, 1940, at the Mission Inn in Riverside, California.[20] She said that she had been attracted to the young Nixon because he "was going places, he was vital and ambitious ... he was always doing things".[8] Later, referring to Richard Nixon, she said, "Oh but you just don't realize how much fun he is! He's just so much fun!" Following a brief honeymoon in Mexico, the two lived in a small apartment in Whittier.[20] As U.S. involvement in World War II began, the couple moved to Washington, D.C., with Richard taking a position as a lawyer for the Office of Price Administration (OPA); Pat worked as a secretary for the American Red Cross, but also qualified as a price analyst for the OPA.[20] He then joined the United States Navy, and while he was stationed in San Francisco, she resumed work for the OPA as an economic analyst.[20]

Veteran UPI reporter Helen Thomas suggested that in public, the Nixons "moved through life ritualistically", but privately, however, they were "very close".[21] In private, Richard Nixon was described as being "unabashedly sentimental", often praising Pat for her work, remembering anniversaries and surprising her with frequent gifts.[21] During state dinners, he ordered the protocol changed so that Pat could be served first.[22] Pat, in turn, felt that her husband was vulnerable and sought to protect him, although she did have a nickname for him which he despised, so she rarely used it: "Little Dicky".[22] Of his critics, she said that "Lincoln had worse critics. He was big enough not to let it bother him. That's the way my husband is."[22]

Pat campaigned at her husband's side in 1946 when he entered politics and successfully ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. That same year, she gave birth to a daughter and namesake, Patricia, known as Tricia. In 1948, Pat had the couple's second and last child, Julie. When asked about her husband's career, Pat once stated, "The only thing I could do was help him, but [politics] was not a life I would have chosen."[23] Pat participated in the campaign by doing research on his opponent, incumbent Jerry Voorhis.[1] She also wrote and distributed campaign literature.[24] Nixon was elected in his first campaign to represent California's 12th congressional district. During the next six years, Pat saw her husband move from the U.S. House of Representatives to the United States Senate, and then be nominated as Dwight D. Eisenhower's vice presidential candidate.

Although Pat Nixon was a Methodist, she and her husband attended whichever Protestant church was nearest to their home, especially after moving to Washington. They attended the Metropolitan Memorial Methodist Church because it sponsored her daughters' Brownie troop, occasional Baptist services with Billy Graham, and Norman Vincent Peale's Marble Collegiate Church.[25]

Second Lady of the United States, 1953–1961

[edit]

At the time of her husband coming under consideration for the vice presidential nomination, Pat Nixon was against her husband accepting the selection, as she despised campaigns and had been relieved that as a newly elected senator he would not have another one for six years.[26] She thought she had prevailed in convincing him, until she heard the announcement of the pick from a news bulletin while at the 1952 Republican National Convention.[26] During the presidential campaign of 1952, Pat Nixon's attitude toward politics changed when her husband was accused of accepting illegal campaign contributions. Pat encouraged him to fight the charges, and he did so by delivering the famed "Checkers speech", so-called for the family's dog, a cocker spaniel given to them by a political supporter. This was Pat's first national television appearance, and she, her daughters, and the dog were featured prominently. Defending himself as a man of the people, Nixon stressed his wife's abilities as a stenographer,[16] then said, "I should say this, that Pat doesn't have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat, and I always tell her she would look good in anything."[27][28]

Pat Nixon accompanied her husband abroad during his vice presidential years. She traveled to 53 nations, often bypassing luncheons and teas and instead visiting hospitals, orphanages, and even a leper colony in Panama.[1] On a trip to Venezuela, crowds pelted the Nixons' limousine with rocks and spit on the couple for being representatives of the U.S. government.[9]

A November 1, 1958, article in The Seattle Times was typical of the media's favorable coverage of the future first lady, stating that "Mrs. Nixon is always reported to be gracious and friendly. And she sure is friendly. She greets a stranger as a friend. She doesn't just shake hands but clasps a visitor's hand in both her hands. Her manner is direct ... Mrs. Nixon also upheld her reputation of always looking neat, no matter how long her day has been." A year and a half later, during her husband's campaign for the presidency, The New York Times called her "a paragon of wifely virtues" whose "efficiency makes other women feel slothful and untalented".[29]

Pat Nixon was named Outstanding Homemaker of the Year (1953), Mother of the Year (1955), and the Nation's Ideal Housewife (1957). She once said that, on a rare evening to herself, she pressed all of her husband's suits, adding, "Of course, I didn't have to. But when I don't have work to do, I just think up some new project."[8]

Her husband's campaigns—1960, 1962 and 1968

[edit]In the 1960 election, Vice President Nixon ran for president of the United States against Democratic opponent Senator John F. Kennedy. Pat was featured prominently in the effort; an entire advertising campaign was built around the slogan "Pat for First Lady".[1] Nixon conceded the election to Kennedy, although the race was very close and there were allegations of voter fraud. Pat had urged her husband to demand a recount of votes, though Nixon declined.[30] Pat was most upset about the television cameras, which recorded her reaction when her husband lost—"millions of television viewers witnessed her desperate fight to hold a smile upon her lips as her face came apart and the bitter tears flowed from her eyes", as one reporter put it.[8] This permanently dimmed Pat Nixon's view of politics.[1]

In 1962, the Nixons embarked on another campaign, this time for Governor of California. Prior to Richard Nixon's announcement of his candidacy, Pat's brother Tom Ryan said, "Pat told me that if Dick ran for governor she was going to take her shoe to him."[31] She eventually agreed to another run, citing that it meant a great deal to her husband,[31] but Richard Nixon lost the gubernatorial election to Pat Brown.

Six years later, Richard Nixon ran again for the presidency. Pat was reluctant to face another campaign, her eighth since 1946.[32] Her husband was a deeply controversial figure in American politics,[33] and Pat had witnessed and shared the praise and vilification he had received without having established an independent public identity for herself.[16] Although she supported him in his career, she feared another "1960", when Nixon lost to Kennedy.[32] She consented, however, and participated in the campaign by traveling on campaign trips with her husband.[34] Richard Nixon made a political comeback with his narrow presidential victory of 1968 over Vice-President Hubert Humphrey—and the country had a new First Lady.

First Lady of the United States, 1969–1974

[edit]Major initiatives

[edit]Pat Nixon felt that the First Lady should always set a public example of high virtue as a symbol of dignity, but she refused to revel in the trappings of the position.[35] When considering ideas for a project as First Lady, Pat refused to do (or be) something simply to emulate her predecessor, Lady Bird Johnson.[36] She decided to continue what she called "personal diplomacy", which meant traveling and visiting people in other states or other nations.[37]

One of her major initiatives as First Lady was the promotion of volunteerism, in which she encouraged Americans to address social problems at the local level through volunteering at hospitals, civic organizations, and rehabilitation centers.[38] She stated, "Our success as a nation depends on our willingness to give generously of ourselves for the welfare and enrichment of the lives of others."[39] She undertook a "Vest Pockets for Volunteerism" trip, where she visited ten different volunteer programs.[39] Susan Porter, in charge of the First Lady's scheduling, noted that Pat "saw volunteers as unsung heroes who hadn't been encouraged or given credit for their sacrifices and who needed to be".[39] Her second volunteerism tour—she traveled 4,130 miles (6,647 km) within the United States—helped to boost the notion that not all students were protesting the Vietnam War.[40] She herself belonged to several volunteer groups, including Women in Community Services and Urban Services League,[39] and was an advocate of the Domestic Volunteer Service Act of 1973,[1] a bill that encouraged volunteerism by providing benefits to a number of volunteer organizations.[41] Some reporters viewed her choice of volunteerism as safe and dull compared to the initiatives undertaken by Lady Bird Johnson and Jacqueline Kennedy.[42]

Pat Nixon became involved in the development of recreation areas and parkland, was a member of the President's Committee on Employment of the Handicapped, and lent her support to organizations dedicated to improving the lives of handicapped children.[1] For her first Thanksgiving in the White House, Pat organized a meal for 225 senior citizens who did not have families.[43] The following year, she invited wounded servicemen to a second annual Thanksgiving meal in the White House.[43] Though presidents since George Washington had been issuing Thanksgiving proclamations, Pat became the only First Lady to issue one.[43]

Life in the White House

[edit]

After her husband was elected president in 1968, Pat Nixon met with the outgoing First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson. Together, they toured the private quarters of the White House on December 12.[44] She eventually asked Sarah Jackson Doyle, an interior decorator who had worked for the Nixons since 1965 and who decorated the family's 10-room apartment on Fifth Avenue in New York with French and English antiques, to serve as a design consultant.[45] She hired Clement Conger from the State Department to be the Executive Mansion's new curator, replacing James Ketchum, who had been hired by Jacqueline Kennedy.[46]

Pat Nixon developed and led a coordinated effort to improve the authenticity of the White House as an historic residence and museum. She added more than 600 paintings, antiques and furnishings to the Executive Mansion and its collections, the largest number of acquisitions by any administration;[1] this greatly, and dramatically, expanded upon Jacqueline Kennedy's more publicized efforts. She created the Map Room and renovated the China room, and refurbished nine other rooms, including the Red Room, Blue Room and Green Room.[47] She worked with engineers to develop an exterior lighting system for the entire White House, making it glow a soft white.[47] She ordered the American flag atop the White House flown day and night, even when the president was not in residence.[47]

She ordered pamphlets describing the rooms of the house for tourists so they could understand everything, and had them translated into Spanish, French, Italian and Russian for foreigners.[47] She had ramps installed for the handicapped and physically disabled. She instructed the police who served as tour guides to attend sessions at the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library (to learn how tours were guided "in a real museum"),[47] and arranged for them to wear less menacing uniforms, with their guns hidden underneath.[47] The tour guides were to speak slowly to deaf groups, to help those who lip-read, and Pat ordered that the blind be able to touch the antiques.[47]

The First Lady had long been irritated by the perception that the White House and access to the President and First Lady were exclusively for the wealthy and famous;[47] she routinely came down from the family quarters to greet tourists, shake hands, sign autographs, and pose for photos.[48] Her daughter Julie Eisenhower reflected, "she invited so many groups to the White House to give them recognition, not famous ones, but little-known organizations..."[49]

She invited former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and her children Caroline and John Jr. to dine with her family and view the White House's official portraits of her and her husband, the late President Kennedy.[50] It was the first time that the three Kennedys had returned to the White House since the president's assassination eight years earlier.[51][52] Pat had ordered the visit to be kept secret from the media until after the trip's conclusion in an attempt to maintain privacy for the Kennedys. She also invited President Kennedy's mother Rose Kennedy to see her son's official portrait.[50]

She opened the White House for evening tours so that the public could see the interior design work that had been implemented. The tours that were conducted in December displayed the White House's Christmas decor. In addition, she instituted a series of performances by artists at the White House in varied American traditions, from opera to bluegrass; among the guests were The Carpenters in 1972. These events were described as ranging from "creative to indifferent, to downright embarrassing".[8] When they entered the White House in 1969, the Nixons began inviting families to non-denominational Sunday church services in the East Room of the White House.[47] She also oversaw the White House wedding of her daughter, Tricia, to Edward Ridley Finch Cox in 1971.[53]

In October 1969, she announced her appointment of Constance Stuart as her staff director and press secretary.[54] To the White House residence staff, the Nixons were perceived as more stiff and formal than other first families, but nonetheless kind.[55]

She spoke out in favor of women running for political office and encouraged her husband to nominate a woman to the Supreme Court, saying "woman power is unbeatable; I've seen it all across this country".[56] She was the first of the American First Ladies to publicly support the Equal Rights Amendment,[57] though her views on abortion were mixed. Following the Court's 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, Pat stated she was pro-choice.[1] However, in 1972, she said, "I'm really not for abortion. I think it's a personal thing. I mean abortion on demand—wholesale."[58]

In 1972, she became the first Republican First Lady to address a national convention.[1] Her efforts in the 1972 reelection campaign—traveling across the country and speaking on behalf of her husband—were copied by future candidates' spouses.[1]

Travels

[edit]

Pat Nixon held the record as the most-traveled First Lady until her mark was surpassed by Hillary Rodham Clinton.[1] In President Nixon's first term, Pat traveled to 39 of 50 states, and in the first year alone, shook hands with a quarter of a million people.[59] She undertook many missions of goodwill to foreign nations as well. Her first foreign trip took in Guam, India, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Pakistan, Romania, and England.[60] On such trips, Pat refused to be serviced by an entourage, feeling that they were an unnecessary barrier and a burden for taxpayers.[60] Soon after, during a trip to South Vietnam, Pat became the first First Lady to enter a combat zone.[1] She had tea with the wife of President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu in a palace, visited an orphanage, and lifted off in an open-door helicopter—armed by military guards with machine guns—to witness U.S. troops fighting in a jungle below.[60] She later admitted to experiencing a "moment of fear going into a battle zone", because, as author and historian Carl Sferrazza Anthony noted, "Pat Nixon was literally in a line of fire."[60] She later visited an army hospital, where, for two hours, she walked through the wards and spoke with each wounded patient.[21] The First Lady of South Vietnam, Madame Thieu, said Pat Nixon's trip "intensified our morale".[21]

After hearing about the Great Peruvian earthquake of 1970, which caused an avalanche and additional destruction, Pat initiated a "volunteer American relief drive" and flew to the country, where she aided in taking relief supplies to earthquake victims.[61] She toured damaged regions and embraced homeless townspeople; they trailed her as she climbed up hills of rubble and under fallen beams.[62] Her trip was heralded in newspapers around the world for her acts of compassion and disregard for her personal safety or comfort,[8] and her presence was a direct boost to political relations. One Peruvian official commented: "Her coming here meant more than anything else President Nixon could have done,"[48] and an editorial in Peru's Lima Prensa said that Peruvians could never forget Pat Nixon.[48] Fran Lewine of the Associated Press wrote that no First Lady had ever undertaken a "mercy mission" resulting in such "diplomatic side effects".[48] On the trip, the Peruvian government presented her with the Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun, the highest Peruvian distinction and the oldest such honor in the Americas.[1]

She became the first First Lady to visit Africa in 1972, on a 10,000-mile (16,093 km), eight-day journey to Ghana, Liberia, and the Ivory Coast.[63] Upon arrival in Liberia, Pat was honored with a 19-gun salute, a tribute reserved only for heads of government, and she reviewed troops.[63] She later donned a traditional native costume and danced with locals. She was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Most Venerable Order of Knighthood, Liberia's highest honor.[63] In Ghana, she again danced with local residents, and addressed the nation's Parliament.[63] In the Ivory Coast, she was met by a quarter of a million people shouting "Vive Madame Nixon!"[63] She conferred with leaders of all three African nations.[63] Upon her return home, White House staffer Charles Colson sent a memo to the President reading in part, "Mrs. Nixon has now broken through where we have failed ... People—men and women—identify with her, and in return with you."[64]

Another notable journey was the Nixons' historic visit to the People's Republic of China in 1972. While President Nixon was in meetings, Pat toured through Beijing in her red coat. According to Carl Sferrazza Anthony, China was Pat Nixon's "moment", her turning point as an acclaimed First Lady in the United States.[65] She accompanied her husband to the Nixon–Brezhnev summit meetings in the Soviet Union later in the year. Though security constraints left her unable to walk freely through the streets as she did in China, Pat was still able to visit with children and walk arm-in-arm with Soviet First Lady Viktoria Brezhneva.[65] Later, she visited Brazil and Venezuela in 1974 with the unique diplomatic standing of personal representative of the president. The Nixons' last major trip was in June 1974, to Austria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Israel, and Jordan.[66]

Fashion and style

[edit]

The traditional role of a First Lady as the nation's hostess puts her personal appearance and style under scrutiny, and the attention to Pat was lively. Women's Wear Daily stated that Pat had a "good figure and good posture", as well as "the best-looking legs of any woman in public life today".[67] Some fashion writers tended to have a lackluster opinion of her well tailored, but nondescript, American-made clothes. "I consider it my duty to use American designers", she said,[68] and favored them because, "they are now using so many materials which are great for traveling because they're non crushable".[69] She preferred to buy readymade garments rather than made-to-order outfits. "I'm a size 10," she told The New York Times. "I can just walk in and buy. I've bought things in various stores in various cities. Only some of my clothes are by designers."[56] She did, however, wear the custom work of some well-known talents, notably Geoffrey Beene, at the suggestion of Clara Treyz, her personal shopper.[56] Many fashion observers concluded that Pat Nixon did not greatly advance the cause of American fashion. Nixon's yellow-satin inaugural gown by Harvey Berin was criticized as "a schoolteacher on her night out", but Treyz defended her wardrobe selections by saying, "Mrs. Nixon must be ladylike."[70][71]

Nixon did not sport the outrageous fashions of the 1970s, because she was concerned about appearing conservatively dressed, especially as her husband's political star rose. "Always before, it was sort of fun to get some ... thing that was completely different, high-style", she told a reporter. "But this is not appropriate now. I avoid the spectacular."[72]

Watergate

[edit]At the time the Watergate scandal broke to the media, Nixon "barely noticed" the reports of a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters.[73] Later, when asked by the press about Watergate, she replied curtly, "I know only what I read in the newspapers."[74] In 1974, when a reporter asked "Is the press the cause of the president's problems?", she shot back, "What problems?"[75] Privately, she felt that the power of her husband's staff was increasing, and President Nixon was becoming more removed from what was occurring in the administration.[74]

Pat Nixon did not know of the secret tape recordings her husband had made. Julie Nixon Eisenhower stated that the First Lady would have ordered the tapes destroyed immediately, had she known of their existence.[76] Once she did learn of the tapes, she vigorously opposed making them public, and compared them to "private love letters—for one person alone".[77] Believing in her husband's innocence, she also encouraged him not to resign and instead fight all the impeachment charges that were eventually leveled against him. She said to her friend Helene Drown, "Dick has done so much for the country. Why is this happening?"[66]

After President Nixon told his family he would resign the office of the presidency, she replied "But why?"[78] She contacted White House curator Clement Conger to cancel any further development of a new official china pattern from the Lenox China Company, and began supervising the packing of the family's personal belongings.[79] On August 7, 1974, the family met in the solarium of the White House for their last dinner. Pat sat on the edge of a couch and held her chin high, a sign of tension to her husband.[80] When the president walked in, she threw her arms around him, kissed him, and said, "We're all very proud of you, Daddy."[80] Later Pat Nixon said of the photographs taken that evening, "Our hearts were breaking and there we are smiling."[81]

On the morning of August 9 in the East Room, Nixon gave a televised 20-minute farewell speech to the White House staff, during which time he read from Theodore Roosevelt's biography and praised his own parents.[82] The First Lady could hardly contain her tears; she was most upset about the cameras, because they recorded her anguish, as they had during the 1960 election defeat. The Nixons walked onto the Executive Mansion's South Lawn with Vice President Gerald Ford and Betty Ford. The outgoing president departed from the White House on Marine One. As the family walked towards the helicopter, Pat, with one arm around her husband's waist and one around Betty's, said to Betty "You'll see many of these red carpets, and you'll get so you hate 'em."[83] The helicopter transported them to Andrews Air Force Base; from there they flew to California.[84]

Pat Nixon later told her daughter Julie, "Watergate is the only crisis that ever got me down ... And I know I will never live to see the vindication."[85]

Public perception

[edit]

Historian Carl Sferrazza Anthony noted that ordinary citizens responded to, and identified with, Pat Nixon.[48] When a group of people from a rural community visited the White House to present a quilt to the First Lady, many were overcome with nervousness; upon hearing their weeping, Pat hugged each individual tightly, and the tension dissipated.[48] When a young boy doubted that the Executive Mansion was her house because he could not see her washing machine, Pat led him through the halls and up an elevator, into the family quarters and the laundry room.[48] She mixed well with people of different races, and made no distinctions on that basis.[64] During the Nixons' trip to China in 1972, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai was sufficiently smitten with her so as to give two rare giant pandas to the United States as a gift from China.[65]

Pat Nixon was listed on the Gallup Organization's top-ten list of the most admired women fourteen times, from 1959 to 1962 and 1968 to 1979.[86] She was ranked third in 1969, second in 1970 and 1971, and first in 1972. She remained on the top-ten list until 1979, five years after her husband left office.[86] To many, she was seen as an example of the "American Dream", having risen from a poor background, with her greatest popularity among the "great silent majority" of voters.[73] Mary Brooks, the director of the United States Mint and a long-time friend of Pat's, illustrated some of the cultural divides present at the time when she described the First Lady as "a good example to the women of this country–if they're not part of those Women's Liberation groups".[8] Additionally, it was the view of veteran UPI correspondent Helen Thomas that Pat "was the warmest First Lady I covered and the one who loved people the most. I think newspeople who covered her saw a woman who was sharp, responsive, sensitive."[87]

Press accounts framed Pat Nixon as an embodiment of Cold War domesticity, in stark contrast to the second-wave feminism of the time.[88] Journalists often portrayed her as dutiful and selfless[89] and seeing herself as a wife first and individual second.[42] Time magazine described her as "the perfect wife and mother–pressing [her husband's] pants, making dresses for daughters Tricia and Julie, doing her own housework even as the Vice President's wife".[90] In the early years of her tenure as First Lady she was tagged "Plastic Pat", a derogatory nickname applied because, according to critics, she was always smiling while her face rarely expressed emotion[91][92] and her body language made her seem reserved, and at times, artificial.[93] Some observers described Pat Nixon as "a paper doll, a Barbie doll–plastic, antiseptic, unalive" and that she "put every bit of the energy and drive of her youth into playing a role, and she may no longer recognize it as such".[8]

As for the criticisms, she said, "I am who I am and I will continue to be."[8] She unguardedly revealed some of her opinions of her own life in a 1968 interview aboard a campaign plane with Gloria Steinem: "Now, I have friends in all the countries of the world. I haven't just sat back and thought of myself or my ideas or what I wanted to do. Oh no, I've stayed interested in people. I've kept working. Right here in the plane I keep this case with me, and the minute I sit down, I write my thank you notes. Nobody gets by without a personal note. I don't have time to worry about who I admire or who I identify with. I've never had it easy. I'm not like all you ... all those people who had it easy."[16]

Despite her largely demure public persona as a traditional wife and homemaker, she was not as self-effacing and timid as her critics often claimed. When a news photographer wanted her to strike yet another pose while wearing an apron, she firmly responded, "I think we've had enough of this kitchen thing, don't you?"[94] Some journalists, such as columnist and White House Correspondent Robert E. Thompson, felt that Pat was an ideal balance for the 1970s; Thompson wrote that she proved that "women can play a vital role in world affairs" while still retaining a "feminine manner".[73] Other journalists felt that Pat represented the failings of the feminine mystique, and portrayed her as being out of step with her times.[89] Those who opposed the Vietnam War identified her with the Nixon administration's policies, and, as a result, occasionally picketed her speaking events. After she had spoken to some of them in one instance in 1970, however, one of the students told the press that "she wanted to listen. I felt like this is a woman who really cares about what we are doing. I was surprised."[95] Veteran CBS correspondent Mike Wallace expressed regret that the one major interview he was never able to conduct was that of Pat Nixon.[96]

Later life

[edit]

After returning to San Clemente, California, in 1974 and settling into the Nixons' home, La Casa Pacifica, Pat Nixon rarely appeared in public and only granted occasional interviews to the press. In late May 1975, Pat went to her girlhood hometown of Artesia to dedicate the Patricia Nixon Elementary School.[97] In her remarks, she said, "I'm proud to have the school carry my name. I always thought that only those who have gone had schools named after them. I am happy to tell you that I'm not gone—I mean, not really gone."[97] It was Pat's only solo public appearance in five and a half years in California.[97]

On July 7, 1976, at La Casa Pacifica, Nixon suffered a stroke, which resulted in the paralysis of her entire left side. Physical therapy enabled her to eventually regain all movement.[1] She said that her recovery was "the hardest thing I have ever done physically".[98] In 1979, she and her husband moved to a townhouse on East 65th Street in Manhattan, New York.[99] They lived there only briefly and in 1981 moved to a 6,000 square feet (557 m2) house in Saddle River, New Jersey.[99] This gave the couple additional space, and enabled them to be near their children and grandchildren.[99] Pat, however, sustained another stroke in 1983[100] and two lung infections the following year.[101]

Appearing "frail and slightly bent",[102] she appeared in public for the opening of the Richard Nixon Library & Birthplace (now Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum) in Yorba Linda, California, on July 19, 1990. The dedication ceremony included 50,000 friends and well-wishers, as well as former Presidents Ford, Reagan, and Bush and their wives.[103] The library includes a Pat Nixon room, a Pat Nixon amphitheater, and rose gardens planted with the red-black Pat Nixon Rose developed by a French company in 1972, when she was first lady.[104] Pat also attended the opening of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California, in November 1991. Former First Lady Barbara Bush reflected, "I loved Pat Nixon, who was a sensational, gracious, and thoughtful First Lady",[105] and at the dedication of the Reagan Library, Bush remembered, "There was one sad thing. Pat Nixon did not look well at all. Through her smile you could see that she was in great pain and having a terrible time getting air into her lungs."[106]

The Nixons moved to a gated complex in Park Ridge, New Jersey, in 1991. Pat's health was failing, and the house was smaller and contained an elevator.[99] A heavy smoker most of her adult life who nevertheless never allowed herself to be seen with a cigarette in public,[104] she eventually endured bouts of oral cancer,[107] emphysema, and ultimately lung cancer, with which she was diagnosed in December 1992 while hospitalized with respiratory problems.[6]

Death and funeral

[edit]Pat Nixon died at her Park Ridge, New Jersey, home at 5:45 a.m. on June 22, 1993, the day after her fifty-third wedding anniversary.[108] She was 81 years old. Her daughters and husband were by her side.

The funeral service for Pat Nixon took place on the grounds of the Richard Nixon Library in Yorba Linda on June 26, 1993. Speakers at the ceremony, including California Governor Pete Wilson, Kansas senator Bob Dole, and the Reverend Dr. Billy Graham, eulogized the former First Lady. In addition to her husband and immediate family, former presidents Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford and their wives, Nancy and Betty, were also in attendance.[109] President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton did not attend the funeral and former presidents Jimmy Carter and George H. W. Bush and their wives Rosalynn and Barbara also did not attend. Lady Bird Johnson was unable to attend because she was in the hospital recovering from a stroke, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis did not attend either.[109] President Nixon sobbed openly, profusely, and at times uncontrollably during the ceremony. It was a rare display of emotion from the former president, and Helen McCain Smith and Ed Nixon both said they had never seen him more distraught.[110][111]

Nixon's tombstone gives her name as "Patricia Ryan Nixon", the name by which she was popularly known. Her husband survived her by ten months, dying on April 22, 1994. He was also 81.[112] Her epitaph reads:

Even when people can't speak your language, they can tell if you have love in your heart.

Popular culture impact

[edit]

In 1994, the Pat Nixon Park was established in Cerritos, California. The site where her girlhood home stood is on the property.[38] The Cerritos City Council voted in April 1996 to erect a statue of the former first lady, one of the few statues created in the image of a first lady.[113]

Pat has been portrayed by Joan Allen in the 1995 film Nixon (for which Allen earned a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress), Patty McCormack in the 2008 film Frost/Nixon and Nicole Sullivan in the 2009 film Black Dynamite. She was sung by soprano Carolann Page in John Adams' opera Nixon in China 1987 world premiere in Houston, Texas; a New York Times critic noted that the performance captured "the First Lady's shy mannerisms" while one from the Los Angeles Times described the subject as the "chronically demure First Lady".[114][115] The part was later sung by Scottish soprano Janis Kelly in the 2011 Metropolitan Opera premiere in New York. This New York Times critic wrote that Kelly "was wonderful as Pat Nixon. During the affecting Act II scene in which she is guided by Chinese escorts and journalists to a glass factory, a people's commune and a health clinic, she is finally taken to a school. She speaks of coming from a poor family and tells the obliging children that for a while she was a schoolteacher. In Mr. Adams's tender music, as sung by Ms. Kelly, you sense Mrs. Nixon wistfully pondering the much different life she might have had."[116]

Historical assessments

[edit]Since 1982 Siena College Research Institute has periodically conducted surveys asking historians to assess American first ladies according to a cumulative score on the independent criteria of their background, value to the country, intelligence, courage, accomplishments, integrity, leadership, being their own women, public image, and value to the president.[117] In terms of cumulative assessment, Nixon has been ranked:

- 37th-best of 42 in 1982[118]

- 18th-best of 37 in 1993[118]

- 33rd-best of 38 in 2003[118]

- 35th-best of 38 in 2008[118]

- 33rd-best of 39 in 2014[119]

In the 2014 survey, Nixon and her husband were ranked the 29th-highest out of 39 first couples in terms of being a "power couple".[120]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "First Lady Biography: Pat Nixon". The National First Ladies Library. 2005. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ Halloran, Richard (March 16, 1972). "First Lady of the Land at 60: Thelma Catherine Ryan Nixon, Woman in the News". The New York Times.

- ^ Kinnard, Judith M. (August 20, 1971). "Thelma Ryan's Rise: From White Frame to White House". The New York Times.

- ^ "First Lady Hailed on Return 'Home'". The New York Times. September 6, 1969. p. 18.

- ^ Illustration in a New York Times article by Judith M. Kinnard, entitled "Thelma Ryan's Rise: From White Frame to White House" (August 20, 1971).

- ^ a b c d e "Pat Nixon, Former First Lady, Dies at 81". The New York Times. July 23, 1993. p. D22. Archived from the original on September 21, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ "Pat Nixon Biography". Archived from the original on July 6, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Viorst, Judith (September 13, 1970). "Pat Nixon Is the Ultimate Good Sport". The New York Times. p. SM13. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Silent Partner". Time. February 29, 1960. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ Roderick, Kevin; Lynxwiler, J. Eric (2005). Wilshire Boulevard: Grand Concourse of Los Angeles. Angel City Press. p. 75. ISBN 1-883318-55-6.

- ^ a b "Patricia Ryan Nixon". The White House. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ Thurman, Judith (November 7, 2011). "Pat and Edith: A Fashionable Footnote". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c Swift (2014), p. 15

- ^ David 1978, p. 41.

- ^ a b Johnson, Erskine (October 6, 1959). "Hollywood Today". Park City Daily News. Bowling Green, Kentucky. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Steinem, Gloria (October 28, 1968). "In Your Heart You Know He's Nixon". New York. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), p. 48.

- ^ "Diplomat in High Heels: Thelma Ryan Nixon". The New York Times. July 28, 1959. p. 11.

- ^ Marton (2001), p. 173.

- ^ a b c d Sferrazza, "Thelma Catherine (Patricia) Ryan Nixon", p. 353.

- ^ a b c d Anthony (1991), p. 172

- ^ a b c Anthony (1991), p. 173

- ^ "Pat Nixon: Steel and Sorrow". Time. August 19, 2008. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ^ "The American Presidency". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

- ^ "A Worshiper in the White House". Time. December 6, 1968. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Ambrose, Stephen E. (1988). Nixon Volume I: The Education of a Politician 1913–1962. Simon & Schuster. p. 264. ISBN 978-0671657222.

- ^ "Richard Nixon's Checkers Speech". PBS. 2002–2003. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- ^ In 1968, however, a fashion writer of The New York Times noted that Pat Nixon had purchased a coat made of blonde mink and one of brown-and-black Persian lamb by the furrier Sidney Fink of Blum & Fink. Curtis, Charlotte (December 21, 1968). "Fashion Spotlight Turns to New First Family". The New York Times.

- ^ Bender, Marylin (July 28, 1960). "Pat Nixon: A Diplomat in High Heels". The New York Times. p. 31.

- ^ O'Brien & Suteski (2005), p. 234

- ^ a b Eisenhower (1986), pp. 205–206

- ^ a b Eisenhower (1986), pp. 235, 237

- ^ Mason, Robert (2004). Richard Nixon and the Quest for a New Majority. UNC Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-8078-2905-6.

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), p. 236.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 165

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 168.

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), p. 254.

- ^ a b "Biography of First Lady Pat Nixon". Richard Nixon Library & Birthplace Foundation. 2005. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Anthony (1991), p. 177

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 181.

- ^ "Richard Nixon: Statement on Signing the Domestic Volunteer Service Act of 1973". The American Presidency Project. October 1, 1973. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ a b Burns (2008), p. 125

- ^ a b c Anthony (1991), p. 178

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), pp. 260, 264.

- ^ Reif, Rita (November 30, 1968). "A Decorator for Nixons Gives Julie A Bit of Help". The New York Times.

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), pp. 261, 263.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Anthony (1991), p. 188

- ^ a b c d e f g Anthony (1991), p. 187

- ^ David (1978), p. 128.

- ^ a b Nixon, Richard (2013). RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon. Simon & Schuster. pp. 502–503.

- ^ Seelye, Katherine Q. (July 22, 1999). "Clinton Mistily Recalls Kennedy's White House Visit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan (July 24, 1999). "JFK Jr. visited White House at invitation of Nixon, Reagan". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ Krebs, Alvin (May 11, 1972). "More on the Wedding". The New York Times.

- ^ "Pat Nixon Hires New Press Aid". Chicago Tribune. October 24, 1969. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Brower (2015), pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b c Curtis, Charlotte (July 3, 1968). "Pat Nixon: 'Creature Comforts Don't Matter'". The New York Times.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 194.

- ^ "Mrs. Nixon Asserts Jane Fonda Should Bid Hanoi End War". The New York Times. August 9, 1972.

- ^ O'Brien & Suteski (2005), p. 239.

- ^ a b c d Anthony (1991), p. 171

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 185.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 186.

- ^ a b c d e f Anthony (1991), p. 196

- ^ a b Anthony (1991), p. 197

- ^ a b c Anthony (1991), pp. 199–200

- ^ a b Anthony (1991), p. 215

- ^ "Redoing Pat". Time. January 24, 1969. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Weinman, Martha (September 11, 1960). "First Ladies—In Fashion, Too?". The New York Times.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 192.

- ^ "Pat's Wardrobe Mistress". Time. January 12, 1970. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ Nixon also frequently wore wigs that replicated her short blonde hairstyle, especially on political trips when access to a hairdresser was difficult. Curtis, Charlotte (July 3, 1968). "Pat Nixon: 'Creature Comforts Don't Matter'". The New York Times.

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), p. 187.

- ^ a b c Anthony (1991), p. 201

- ^ a b Anthony (1991), p. 203

- ^ Anthony, C. S. (1991), p. 210

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), pp. 409–410.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 214.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 216.

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), pp. 417–419.

- ^ a b Anthony (1991), p. 217

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), p. 424.

- ^ "Richard M. Nixon: White House Farewell". The History Place. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 218.

- ^ "Nixon's resignation changed American politics forever". CNN. August 9, 1999. Archived from the original on August 29, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), p. 453.

- ^ a b Newport, Frank; David W. Moore & Lydia Saad (December 13, 1999). "Most Admired Men and Women: 1948–1998". Gallup Organization. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 167.

- ^ Burns (2008), pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Burns (2008), pp. 110–111

- ^ Angelo, Bonnie (July 5, 1993). "The Woman in the Cloth Coat". Time. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ "Thelma Nixon". Miller Center of Public Affairs. 2008. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Schmitz, Justin (March 12, 2008). "Secrets will be shared in one-woman show, Lady Bird, Pat & Betty: Tea for Three at Toland theatre". University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Wallace, Mike (2005). "Between You and Me". WNYC Radio. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ Toner, Robin (February 2, 1997). "Running Mates". The New York Times.

- ^ Anthony (1991), p. 182.

- ^ "The one big interview Mike Wallace never landed". USA Today. Associated Press. March 22, 2006. Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ a b c Eisenhower (1986), p. 441

- ^ Eisenhower, Julie (1986), p. 451

- ^ a b c d Coyne, Kevin (May 6, 2007). "Final Days for a Moldy Nixon Retreat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Eisenhower (1986), p. 458.

- ^ "Pat Nixon Is Hospitalized". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 6, 1984. Archived from the original on September 21, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ Apple, R. W. Jr. (July 20, 1990). "Another Nixon Summit, At His Library". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ "Museum Tour: The Museum". Richard Nixon Library Foundation. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "Pat Nixon Dies; Model Political Wife Was 81". Los Angeles Times. June 23, 1993. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- ^ Bush (1994), p. 97.

- ^ Bush (1994), p. 441.

- ^ "Pat Nixon Released From Hospital". The New York Times. February 13, 1987. Archived from the original on September 21, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents. Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration. 1993. p. 1157. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "Funeral Services of Mrs. Nixon". Richard Nixon Library & Birthplace Foundation. 2005. Archived from the original on June 9, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- ^ Thomas (1999), p. 258.

- ^ Brower, Kate Andersen (2016). First Women: The Grace and Power of America's Modern First Ladies. 195 Broadway New York, NY 10007: HarperCollins Publishers Inc. p. 321. ISBN 9780062439666.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Weil, Martin; Randolph, Eleanor (April 23, 1994). "Richard M. Nixon, 37th President, Dies". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ "Pat Nixon Statue at the Cerritos Senior Center". City of Cerritos. 2000. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Henahan, Donal (October 24, 1987). "Opera: Nixon in China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ Bernheimer, Martin (October 24, 1987). "Gala Opera Premiere: John Adams' Nixon in China in Houston". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 31, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (February 4, 2011). "President and Opera, on Unexpected Stages". The New York Times. p. C1. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ "Eleanor Roosevelt Retains Top Spot as America's Best First Lady Michelle Obama Enters Study as 5th, Hillary Clinton Drops to 6th Clinton Seen First Lady Most as Presidential Material; Laura Bush, Pat Nixon, Mamie Eisenhower, Bess Truman Could Have Done More in Office Eleanor & FDR Top Power Couple; Mary Drags Lincolns Down in the Ratings" (PDF). scri.siena.edu. Siena Research Institute. February 15, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2nd Place Hillary moves from 5th to 4th; Jackie Kennedy from 4th to 3rd Mary Todd Lincoln Remains in 36th" (PDF). Siena Research Institute. December 18, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ "Siena College Research Institute/C-SPAN Study of the First Ladies of the United States 2014" (PDF). scri.siena.edu. Siena College Research Institute. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "2014 Power Couple Score" (PDF). scri.siena.edu/. Siena Research Institute/C-SPAN Study of the First Ladies of the United States. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

References

[edit]- Anthony, Carl Sferrazza (1991). First Ladies: The Saga of the Presidents' Wives and Their Power; 1961–1990 (Volume II). New York: William Morrow and Co.

- Brower, Kate Andersen (2015). The Residence: Inside the Private World of The White House. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-230519-0.

- Burns, Lisa M. (2008). First Ladies and the Fourth Estate: Press Framing of Presidential Wives. DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-87580-391-3.

- Bush, Barbara (1994). A Memoir. New York: Scribner.

- David, Lester (1978). The Lonely Lady of San Clemente: The Story of Pat Nixon. Crowell. ISBN 0-690-01688-3.

- Eisenhower, Julie Nixon (1986). Pat Nixon: The Untold Story. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-24424-8.

- Marton, Kati (2001). Hidden Power: Presidential Marriages That Shaped Our History. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 0-375-40106-7.

- O'Brien, Cormac; Suteski, Monika (2005). Secret Lives of the First Ladies: What Your Teachers Never Told You About the Women of the White House. Quirk Books. ISBN 1-59474-014-3.

- Swift, Will (2014). Pat and Dick: The Nixons, An Intimate Portrait of a Marriage. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-7694-5.

- Thomas, Helen (1999). Front Row at the White House: My Life and Times. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-86809-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Anthony, Carl Sferrazza (2001). "Thelma Catherine (Patricia) Ryan Nixon". In Gould, Lewis L. (ed.). American First Ladies: Their Lives and Their Legacy (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Truman, Margaret (1999). First Ladies. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-43439-9.

External links

[edit]- Pat Nixon

- 1912 births

- 1993 deaths

- People from Ely, Nevada

- People from Cerritos, California

- People from the Upper East Side

- People from Park Ridge, New Jersey

- People from Saddle River, New Jersey

- Nixon family

- First ladies of the United States

- Second ladies and gentlemen of the United States

- American Methodists

- American people of German descent

- American people of Irish descent

- Spouses of California politicians

- Retail clerks

- Nevada Republicans

- California Republicans

- New Jersey Republicans

- USC Rossier School of Education alumni

- Fullerton College alumni

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Sun of Peru

- Recipients of the Order of the Pioneers of Liberia

- Marshall School of Business alumni

- Deaths from emphysema

- Deaths from lung cancer in New Jersey

- Tobacco-related deaths

- 20th-century American educators

- 20th-century American politicians

- 20th-century American women educators

- 20th-century Methodists